VISUAL ARTS

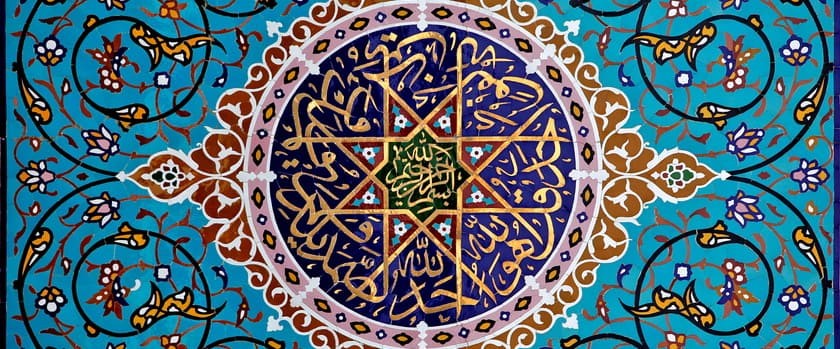

In fact, the Persian miniature, so rich in subtle delicacy as to make her artists use brushes of only one hair, is famous all over the world. It is believed that the origin of this form of art should be traced back to the predilection for painting nourished by the Persian religious leader Mani (216-277 AD). Later, because the Islamic doctrine, even without prohibiting them, did not favor the portraits and depictions of people and events, for the decorations it was preferred to calligraphy, floral motifs, geometric compositions, while the polychrome survived only in ceramics and he painted only to illustrate texts, such as the Qur'an, scientific works, epic poems, legends, panegyrics in praise of the deeds of sovereigns or heroes. At the same time, Persian artists were also influenced by Byzantine manuscripts, especially under the profile of the hieratic immobility of Christian models.

Already in the XI century AD the Persians were considered the undisputed masters of the miniature, and since then they have always remained. In the late fifteenth century and the beginning of the next this art reached the peak of beauty and quality. In the city of Herat (today in Afghanistan. ) were permanently at work 40 calligraphers; to Tabriz a brilliant painter, Behzad, who directed the work of hundreds of artists, succeeded in renewing the miniature by combining the traditional concept of decoration with a special taste for the realistic and the picturesque. The compositions of this period reveal brave expressive talents, above all in the subtle harmony of colors. Scenes composed of a multitude of figures cover large pages without leaving empty; distances are expressed by the overlapping of objects, all equally illuminated, with an overall result of great delicacy and splendid polychrome.

A further step in the evolution of this art occurred thanks to the influence of the painter Reza Abbasi, when in the miniatures a certain degree of naked realism began to emerge. Abbasi was the first artist whose inspiration came directly from the scenes of the streets and the bazaar of Isfahan. In this period the walls of the buildings were covered with frescoes on war themes or lighter subjects, then reproduced more frequently. Excellent examples are preserved in the Palazzo delle Quaranta Colonne (Chehel Sutun) in Isfahan.

In the nineteenth century the miniature gradually began to fall into disuse, partly because of the increasingly strong Western influence. Mirza Baba, official painter of the Qajar court, painted portraits of princes with remarkable expressiveness, but also cassepanche covers, writing desks and mirrors cases where the influence of the centuries-old tradition of miniatures is very evident. In this period also "naif" wall paintings, called "teahouse paintings", began to appear in Iran. These were large frescoes, or sequences of scenes, used as a reference by the storytellers: they illustrated the deeds of the legendary heroes of the Persian epic, rendered immortal by Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, such as Rostam, but also love stories like that of Youssef and Zuleikha, and events in the history of Shiism, in particular the tragedy of Garbala, with the martyrdom of the saint Imam Hossein.

Among other things, the 1978 / 79 Revolution had the merit of encouraging the spread and development of painting, on the one hand by establishing specific courses and faculties in both the state and private school system, restoring museums, supporting the foundation of galleries and special exhibitions, on the other allowing Iranian scholars and artists to turn their attention to the peculiarly Persian pictorial tradition, which the Pahlavi monarchy had stubbornly neglected by imposing the indiscriminate westernization of all the artistic manifestations of the country.

The pre-eminent figure of twentieth-century Iranian painting is Kamal-ol-Molk, who died in 1940 and is considered not only the father of modern national figurative art, but one of the country's most loved symbols. We owe to him, in fact, the radical renewal of Persian painting techniques, the birth of a new concept of style as a desire to overcome tradition, both by revolutionizing the compositional formulas and by assigning to the painting the task of expressing and communicating the "spirit of the ". In fact, his search for realism is never separated from the free course of imagination, expressed in games of perspective and in a rare essentiality of colors - innovations, these, quite courageous in the Persian artistic environment at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. .

Kamal-ol-Molk was born into a family, the Ghaffari-Kashani, of proven artistic talent (his father, his uncle and his brother are still recognized among the most significant personalities in recent Iranian art history); King Qajar Nassreddin Shah soon gave him the title of "Master of Painters", appointing him commander of a cavalry battalion in the province of Qazvin. Here he lives the most productive period of his artistic existence, painting over one hundred and seventy paintings. At the death of the monarch, however, Kamal-ol-Molk, extremely critical of the conditions in which the Qajar keep the country, troubled by corruption and easy prey of the aims of foreign powers, leaves the post and goes to Europe, where it remains for five years.

Nassreddin's successor, Mozafareddin Shah, reaches him to beg him to return home; and Kamal-ol-Molk consents, hoping to contribute to the evolution of the country. He realizes, however, that nothing has changed, especially in the customs of the Court and in the general disorder: after having been patiently struggling for a few months, on the occasion of a religious pilgrimage he leaves Iran again and settles in Iraq for two years. His canvases effectively express the emotions and disdain felt in the face of the conditions of poverty and abandonment in which he saw his people lie.

In the early years of the century, he willingly offered his support for the struggle of the Constitutionalists; and to participate directly in the work of opposition against the monarchy, he returns to his homeland again. In the 1906 the Qajar are forced to launch a Constitution, which will also have to be resolutely defended by attempts to abolish it from the successor Mohammad Ali Shah. With hard work, but with extreme tenacity, Kamal-ol-Molk manages to lay the foundations of a school where those who are interested in art can receive an adequate training: thus born in Iran the first true "School of Fine Arts", where for a certain period he himself works as a teacher, almost always devolving his salary to the poorest students. He loves to repeat: "To the same extent that I teach my students, I learn from them".

The dramatic changes in the political situation and the heavy interference of Russians and Britons who dispute the control of Iran lead to the coup of the 1920 and the subsequent settlement of Reza Khan on the throne at the behest of London. Kamal-ol-Molk immediately realizes that there is no difference in substance between the despotism of the Qajar and that of the newly formed Pahlavi dynasty, and although Reza Shah makes every effort to convince him, he refuses to collaborate with the Court. As a result the shah boycotts his school and creates all sorts of administrative difficulties until, in the 1927, Kamal-ol-Molk is forced to resign. The following year he was exiled to Hosseinabad, a fraction of Neishabour: the forced separation from the students, the artistic and educational activity undermine the body as well as the soul. Following an incident that has remained mysterious, he also loses the use of an eye, and stops painting; he will die in poverty twelve years later.

The research effort developed by contemporary Iranian painters over the last twenty years - research that always includes the utmost attention to Western art, but in a spirit of autonomy and above all without attempts at slavish emulation - is today gradually leading to a clearer delineation. of the main stylistic trends. Taking every care to avoid improper comparisons between the expressive results of different cultural traditions, generated and sustained by different historical paths, and with the sole purpose of allowing the Western reader a first elementary approach, it could be said that it prevails today among Iranian painters. , an expressionist orientation, which sometimes makes use of the stylistic figures of symbolism, sometimes of surrealist ideas. The figurative production then appears often - more or less consciously - influenced by the formulas of graphics, in the search for an extreme essentiality of the stroke, and a use of color as a narrative element. From this starting point, then, some painters willingly take further steps towards a progressive abstraction, or at least a greater stylization of forms.

Observe for example the work of Honibal Alkhas, born in Kermanshah in 1930 and trained at the Art Institute of Chicago after learning the rudiments of art from Alexis Georgis in Arak and from Ja'far Petgar in Teheran. Alkhas likes to affirm that his style consists in "juxtaposing the possible and the impossible", and defining himself as an expressionist, but "eclectic in the broadest sense of the word", therefore open to classical or even surrealistic-romantic suggestions.

Another direction has instead embarked Tahereh Mohebbi Taban, born a Tehran in 1949, today also active in the fields of design, graphics and sculpture, as well as teaching (his works have also been exhibited in Japan and Canada). His attention focuses particularly on the relationship between form and color as a formula for the visual expression of ideas; his preferences go to the contrasts between the hues or the textures, between the thicknesses of the different lines, between the planes in their respective location and distance. As a consequence, its forms are almost always stylized, and the tendency towards a progressive abstraction is very clear, as is the continuous effort of synthesis.

Only apparently different is the path chosen by the fifty-year-old painter and sociologist Farrokhzad. His watercolors are now explicitly referring to the oldest Persian culture, taking up signs and symbols of the pre-Islamic era, especially Achaemenid: the eight-petalled flower, the lion's tail, the wings of the eagle, the bull's horn, the circle as a unifying factor. The different elements are inserted harmoniously on foggy backgrounds, almost dreamlike scenarios, next to shapes depicting goats or winged horses, for a global result that the European observer would tend to define as surrealistic.

If the atmosphere of Farrokhzad's paintings appears altogether serene, almost fairytale, most of the youngest of Iranian contemporary painters, especially of those who have begun to paint during the years of the war of defense against the Iraqi aggression, express with remarkable efficacy, though in sometimes still crude forms, a profound sense of the tragic.

It can be understood when one is able to pass a first level of reading their paintings, where the use of certain symbols too literary (and literal) appears perhaps hasty, immature, or better symptom of an immature stage of research and reflection. The tremendous force, both destructive and creative, of human suffering becomes plasticity of lines and brushstrokes, in the deformation of the faces, in the writhing of the bodies, and the vibrations of the colors are only the prolongation of agonizing screams.

Nasser Palangi (Hamadan, 1957) paints choral scenes of earthly pain that recall the minds of Dantesche enveloped in flames; Kazem Chalipa (Tehran, 1957) conceives the bowels of the Earth as one gigantic dark den of dis / human creatures with faces like rats' faces, and its surface like a desolate land where strange ferocious vultures attack fleeing men; Hossein Khosrojerdi (Tehran, 1957) multiplies the Scream of Munch on the faces of figures that are not mere shapes, because they maintain a measure of reality that makes their despair more "historical" and perhaps more atrocious.

Of this generation of painters, however, the constant attention to social problems, to the dramas of the Iranian population (the war, as it was said; poverty experienced as a condemnation up to the moment of the Revolution), should also be emphasized - or perhaps in the first place. striking contrast between the loneliness of the individual crushed by injustices and the sense of rebirth that is generated by solidarity, and the deeper values of Iranian culture as a whole, from the sense of honor to the concept of freedom as mystical dissolution in the Supreme Being . Probably, precisely in this common character, and in the clear refusal of art "an end in itself", lies the legacy that these young painters intend to collect from the most authentic Persian tradition, a legacy that now awaits to be further refined and made consonant times also on a stylistic level.