THEATRE

The History of Dramatic Art in Iran

The European concept of theater was introduced in Iran only in the twenties of the twentieth century; one can not therefore speak of a Persian tradition in the field, but typical of Iran is a very special form of representation, the ta'zieh.

The word ta'zieh, which originally referred to manifestations of mourning, has come over the course of time to specifically name a tragic representation typical of Persian folk theater, ta'zieh khani (drama of imitation).

The ta'zieh, or sacred representation, flourished in Persia in the epoch of the Shiite Muslim dynasty of the Safavids (1502 - 1736 AD), from much more ancient roots.

It is also known in the West by 1787, that is when an Englishman, William Franklin, visiting Shiraz, describes a representation.

Ta'zieh progresses and flourishes under the protection of the Qajar kings, in particular Nasser ad-Din Shah (1848-96), and is equally well received and actively supported by the general public.

Shah himself builds takiyeh dowlat (that is, as will be seen later on, some special special "state theater spaces") in which the official and more elaborate ta'zieh are represented. This kind of ritual theater acquires so much prestige that an English iranologist, Sir Lewis Pelly, writes: "If we must measure the success of a theatrical representation from the effects it produces on the people for whom it is composed or on the public in front of which it is represented, none has ever surpassed the tragedy known in the Muslim world as that of Hassan and Hossein ". Even other Westerners, like the British Edward Gibbons, TB Macaulay and Mattew Arnold and the French such as Arthur Gobineau and Ernest Renan, pay tributes similar to the Persian religious drama.

From 1808 foreign travelers begin to compare the ta'zieh to the "Mysteries" and to the "Passions" of the European Middle Ages.

In the early Thirties, during the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, the ta'zieh was banned for the officially declared purpose of "avoiding barbaric acts of mass exaltation" and paying tribute to the Turkish Sunnite state.

However, it survives in clandestine form in the most remote villages, re-emerging only after the 1941.

It remains in marginal conditions until the beginning of the Sixties, when intellectuals like Parviz Sayyad begin to make it the object of research, asking for the annulment of the announcement and representing some fragments.

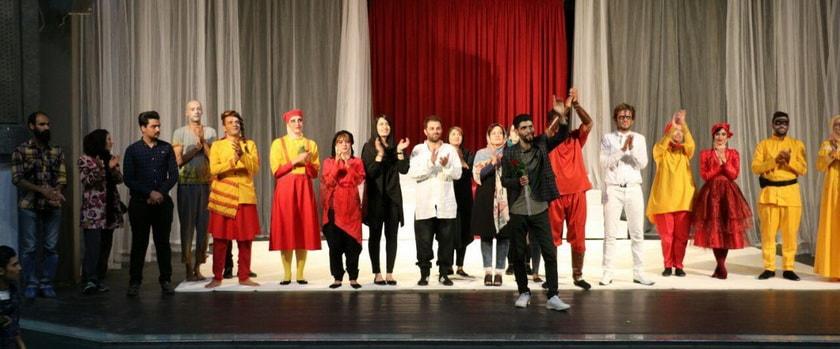

A complete representation of ta'zieh is finally presented during the Shiraz Arts Festival in the 1967; the same Festival, in 1976, promotes an international seminar during which Mohammad Bagher Ghaffari organizes 14 free representations of seven ta'zieh, attended by about 100.000 spectators.

Three large-scale representations of ta'zieh are organized to commemorate the first anniversary of the death of Imam Khomeini, which took place in the 1989, at his Mausoleum, in a takyeh and at the Teatr-e Shahr (City Theater).

The ta'zieh is still represented in Iran, particularly in the central regions of the country (it is not part of the traditions of the eastern and western territories).

Constant and typical subject of ta'zieh is the evocation of the most dramatic phases of life, and of the tragedy of martyrdom, of all the Imam of Shiism (except the XII, still "in occultation"), in particular of the Saint Imam Hossein, killed with his followers and family in Karbala in the month of moharram of the year 61 of the Hegira (683 AD) by the army of the caliph Yazid.

The dramas often tell the journey of the Imam and his people from Medina to Mesopotamia, its battles and its martyrdom.

There are also dramas concerning the Prophet Mohammad and his family and other holy figures, stories from the Qur'an and the Bible.

But the most important character is the Imam Hossein, who plays innocence and is the believer's intercessor.

His purity, his unjust death, his submission to destiny make him worthy of love and adoration.

He is also (like Jesus) the intercessor for humanity on the day of judgment; he sacrifices himself for the redemption of the Muslims.

The ta'zieh that tell stories different from the martyrdom of Imam Hossein are represented at other times of the year other than the month of moharram.

Iranian industry experts believe that the scenography and customs of the ta'zieh refer mainly to the stories of Iranian mythology, in particular to the narratives and descriptions of the Shahnameh ("The Book of Kings") of the greatest Persian poet Ferdowsi.

The scripts are always written in Persian and in verse, for the most part of anonymous authors.

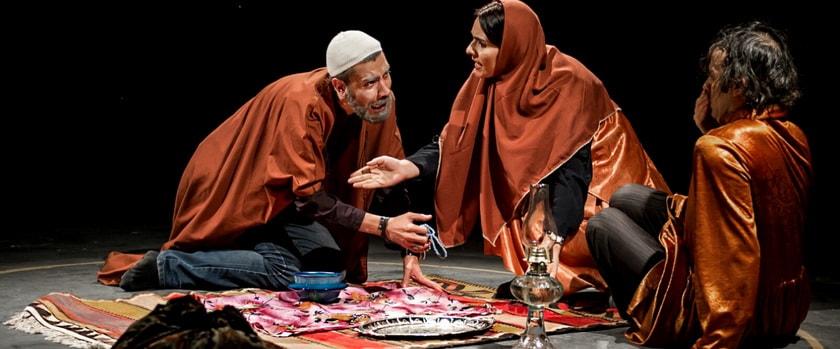

To involve the public more intensely, the authors not only allow themselves to alter the historical facts, but also transform the characters of the protagonists. For example, the Saint Hossein is regularly portrayed as a man who painfully accepts his destiny: crying, he proclaims his own innocence and arouses the cry of the public who, in this ritual performance, in turn complains about his own faults and conditions of oppression. The characters of the "oppressed" and of the "martyr" are the most recurrent "characters", and more able to arouse feelings of compassion and emotional participation among the spectators. In ta'zieh are presented two types of characters: religious and venerable, who are part of the family of the Holy Ali, the first Imam of the Shiites, and are called "Anbia" or "Movafegh Khan"; and their treacherous enemies, called "Ashghia" or "Mokhalef Khan". The actors (more correctly called "readers") who personify the Saints and their followers dress in green or white and sing or recite the verses, accompanied by music; the latter, who wear red clothes, merely declaim them coarsely.

In general, it is not a matter of professional actors, but of people who work in all social sectors and act only on sacred occasions.

Some masks are used, especially that of the devil.

In fact, in ta'ziyeh we can observe the presence of very different theatrical modules, intertwined in a framework of extreme complexity and effectiveness.

It may happen, in the first place, that the actor who impersonates the murderer of the Holy Martyr, suddenly - while he is still dragged by the murderous fury - addresses the spectators crying, shouting at them his pain for the crime actually committed by the real assassin in the past, and denouncing its injustice.

At the same time the role of the narrator is generally held not by an actor but by an exponent of some local association or corporation